Expenses for the government of a developing country usually outstrip its income and India is no exception. The Centre, as well as states, have to borrow from the savers – the households – and finance its expenditure. As with any borrowing, interest has to be paid. And interest payments have historically been a drain on India’s coffers, which is why these will be closely watched in Budget 2023.

Interest payments are the single biggest item of the Centre’s expenditure. In the current financial year, the Centre is set to spend 20 percent of its expenditure on paying interest on its debt. The next big sub-heads are states’ shares of taxes and duties with 17 percent and central sector schemes with 15 percent.

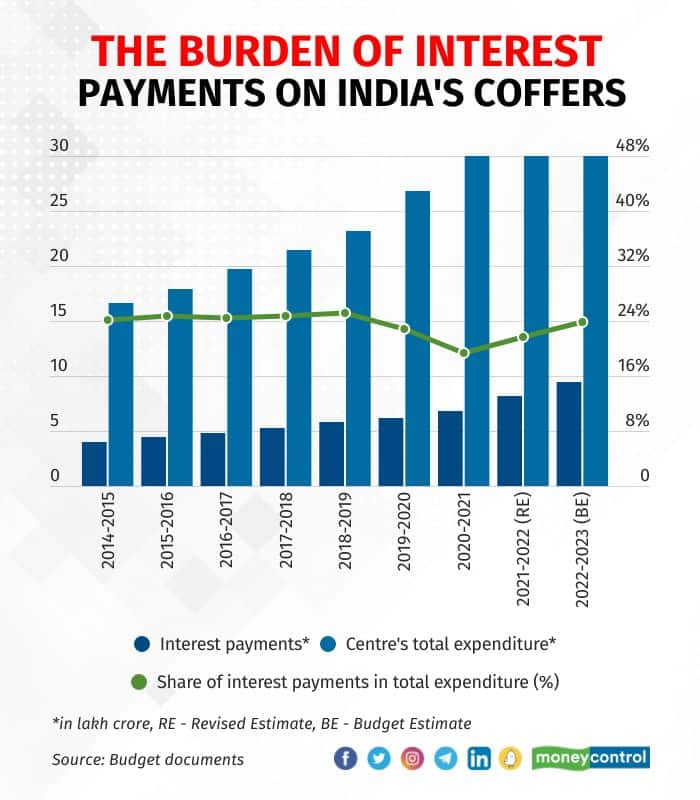

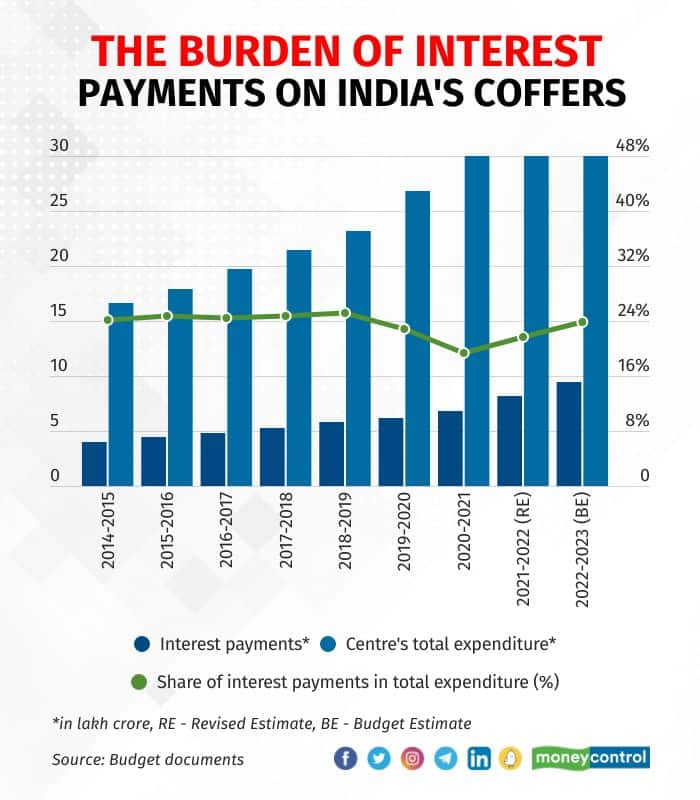

In 2014-15, the Centre paid out Rs 4.02 lakh crore as interest on its debt. While this increased steadily, as would be expected, the last three years have seen a sharp increase in these payments – both in absolute terms as well as a fraction of expenditure.

In 2021-22, the Centre spent Rs 8.14 lakh crore on interest payments, amounting to 21.6 percent of its total expenditure for the year and 39.1 percent of the revenue receipts. Compared to 2020-21, the interest payments were up 19.7 percent.

The rapid rise in the Centre’s interest payments in 2021-22 and 2022-23 is despite the weighted average cost of its borrowing in 2020-21 being 5.79 percent – the lowest in 17 years – thanks to the Reserve Bank of India’s deft management of the yield curve.

The coronavirus pandemic forced the Centre to borrow more as its revenue took a hit and expenditure mounted. Its market borrowing, on a net basis, more than doubled from Rs 4.74 lakh crore in 2019-20 to Rs 11.19 lakh crore this year.

The budgetary estimate for 2022-23 shows the Centre will have to spend Rs 9.40 lakh crore on interest payments. This will be 23.8 percent of the government’s total expenditure and 42.7 percent of its revenue receipts.

The share of interest payments in total expenditure is expected to remain high in 2023-24 as well. The very large share of the pie its take away from the coffers emphasises the need to limit government borrowing and, on the whole, consolidate its finances.

While the government has often argued that the sustainability of its debt is not in question as long nominal GDP growth exceeds the interest it pays on its debt, the fact remains that a high interest burden adds to the government’s committed expenditure and prevents it from spending more on productive areas.